This year I walked 3140 kilometres. This means two hours, 8.6 km per day. I climbed 20 flights of stairs a day, 7300 in total.

This year I also biked a lot.

This year my legs were my main means of locomotion. Elsewise I traveled sparingly: the Sunshine Coast to retreat; Montreal to join in prayer; Ontario to help a church; Washington State to visit a friend; Bella Coola to mourn; the UK to teach.

This year our family took a trip to Lillooet, of which I shall not speak.

This year the devil conspired against us.

This year I lost significantly more than I won. This year I nearly lost everything.

This year our neighbourhood and our garage and the abandoned house next door burned.

This year friends used Northwest Coast Indigenous art to protect us from arson.

This year our children took some hits. I am sorry about that. More will come, because life is like that. I am sorry about that too.

This year faith and family were tested.

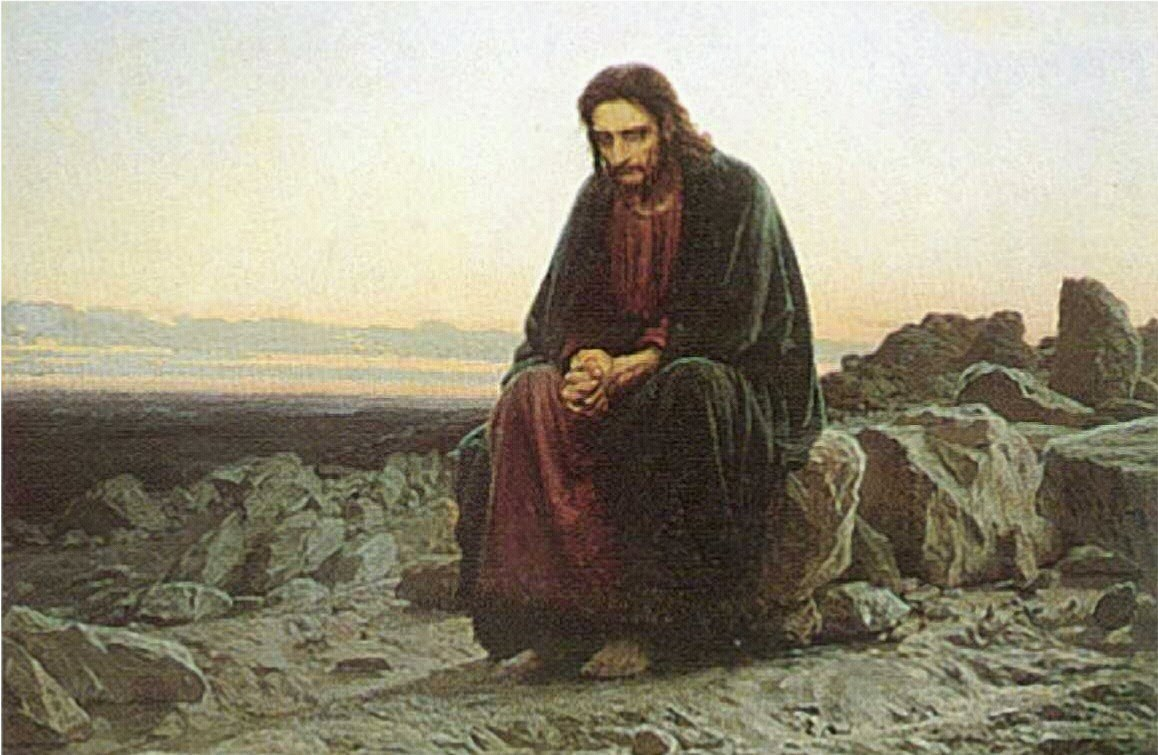

This year I fought some demons. This year I was bloodied.

This year I watched my father die. He died well. But still.

This year I was very, very sad.

This year I sought solace in poetry and in prayer.

This year I prayed the Jesus Prayer every day.

This year I prayed over a large chunk of Vancouver.

This year I learned some things about intercession.

This year I saw some who were dead come back to life.

This year I believed in Sasquatches.

This year I made some new friends, renewed some old friendships, lost some friends.

This year I sat under the teaching of indigenous elders, and began integrating physical, emotional, mental and spiritual directions within myself.

This year I completed a set of steps.

This year I was blessed by my neighbours and community.

This year I went to some great shows: Jack White, Ben Caplan (x2), Nathaniel Rateliff and the Night Sweats, Sigur Ros.

This read I read deeply, watched intently and listened closely.

This year I bailed ankle-deep ice water out of my basement on Christmas Eve.

This year I recorded a song about a baboon.

This year I began writing two books that no one asked for and which may never be completed.

This year I took a break, but did not get a rest.

This year I decided to no longer serve organizations, only people.

This year some people showed great mercy to us. Others did not. I am trying to learn how to be grateful for both.

This year was the hardest.

I am glad to see the back of this year.